The morality of Saudi money in football, part 1

This summer’s biggest football story continues to be the vast sums of money being spent by clubs within Saudi Arabia’s Pro League to attract star names to play in Arabia. The previous post discussed this from the perspective of the sport as a whole, thinking about how Saudi money might (or might not) change the football landscape.

There is, however, an entirely different way in which we might approach these developments, which is to consider how ethically problematic they are and how football — fans, players, regulators — should respond. This is what I’ll do over the course of three posts. In this one, I assess the reasons we might have for objecting to Saudi prominence in the sport; part two argues that our evaluations of this issue need to go beyond picking out hypocrisy; part three considers how we should best respond.

What are the issues here?

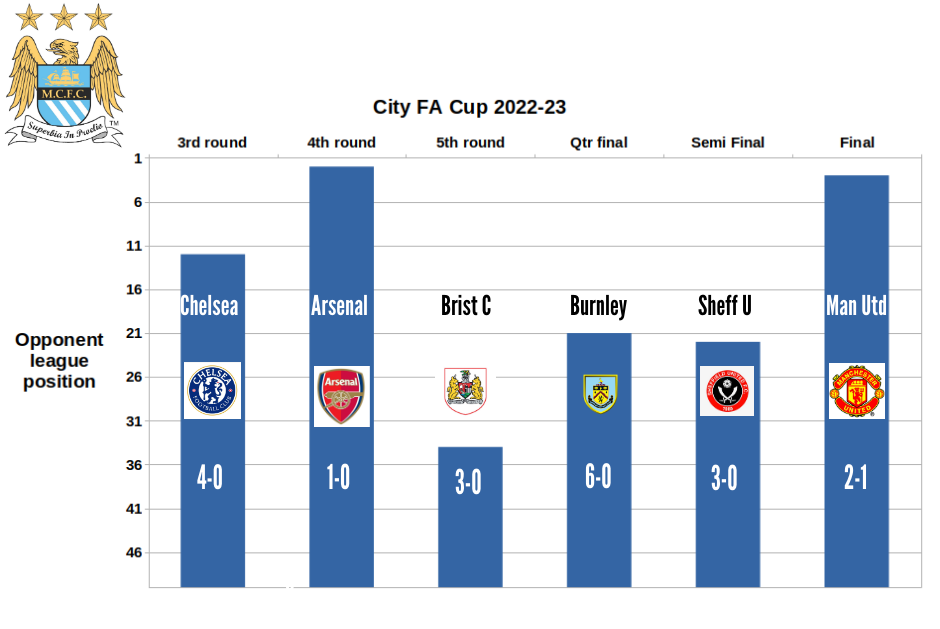

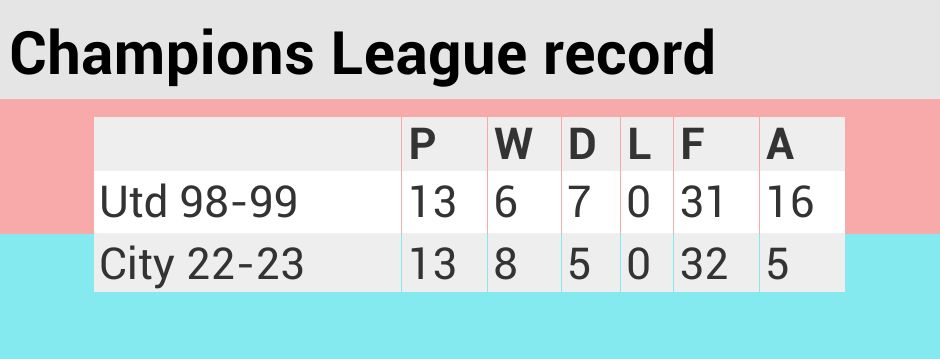

Money from Middle-Eastern petro-states is, of course, not new in football: Manchester City’s current reign of success has been bankrolled by Abu Dhabi, while Qatar, in addition to hosting last year’s World Cup, has also overseen an ownership period at Paris Saint Germain during which the club has pursued a ‘Football Manager on cheat mode’ transfer policy — bringing, among others, Lionel Messi, Kylian Mbappé and Neymar to the French capital — yet has failed to bring the Champions League trophy that would have marked the project as a success. Throughout this period, we have seen increased discussion of the concept of sportswashing as a way of capturing the ethical unease caused by links between sporting events or organisations and entities (especially states) whose wider activities raise significant moral questions.

Under the banner of sportswashing, however, there are a range of different concerns that often get bundled together. I think it is worth distinguishing between the different issues caused by state involvement of this kind, though, to be clear as to the different types of response that might be available.

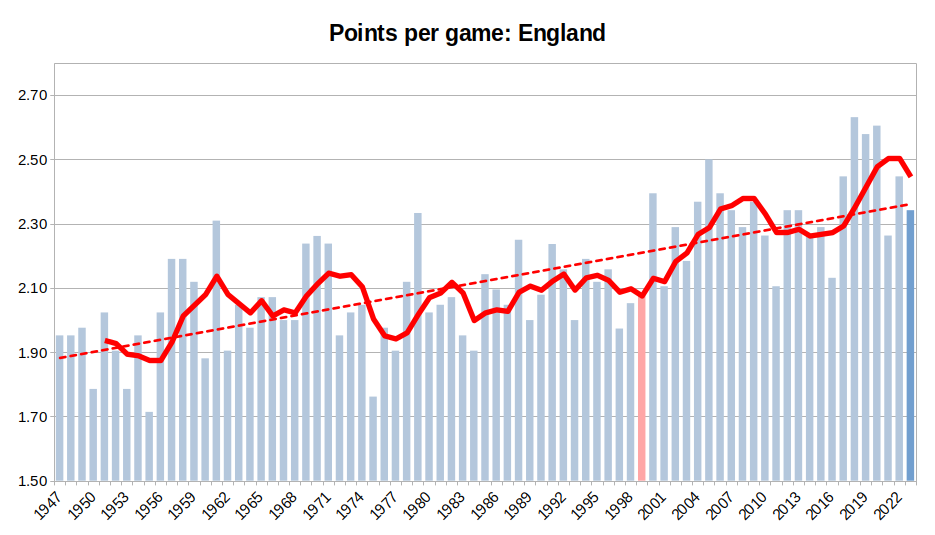

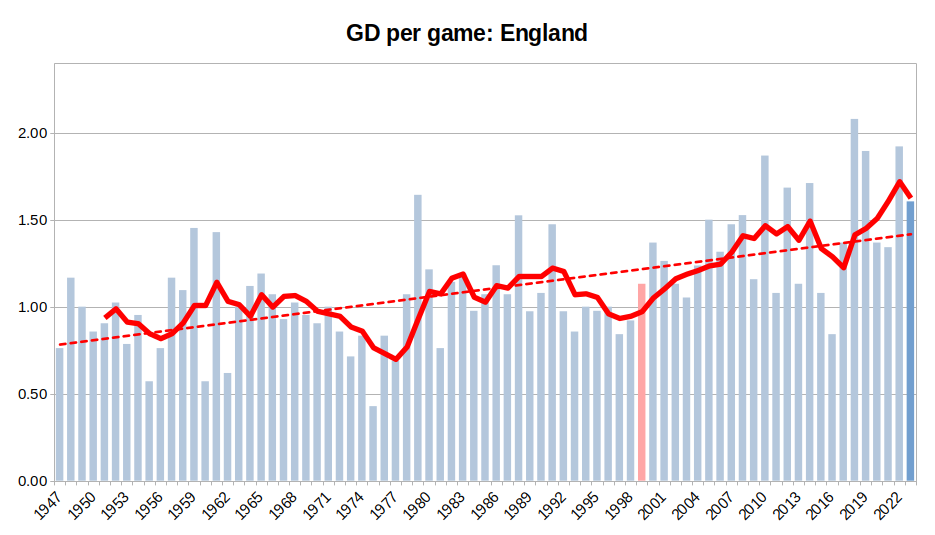

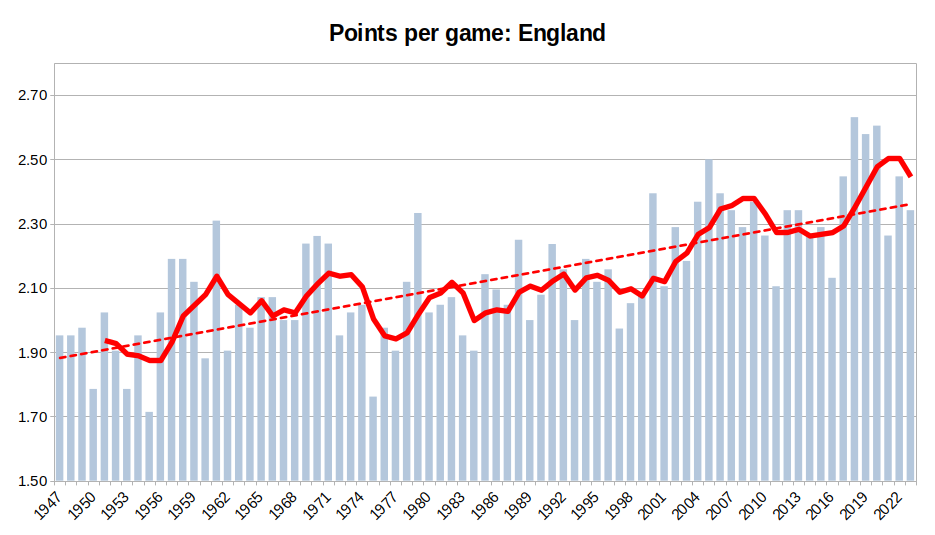

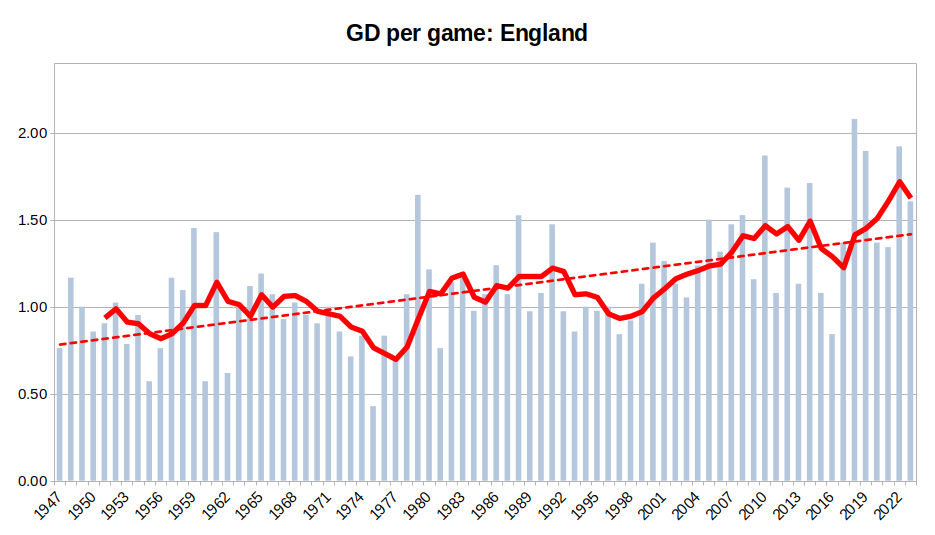

The first level of concern is that state finances, or the sovereign wealth funds through which investment in football usually comes, are generally able to dwarf the wealth of even the richest private individuals, meaning funding of this kind is capable of propelling the clubs it backs straight to the peak of the football transfer market, while in the process bidding-up the transfer fees and wages that top stars are able to command. In short, it turbo-charges the effects of inequality upon levels of competition in the sport. The whole point of this site is to explore how inequality of resources off-the-field impacts what we see on-the-field, so this is certainly an effect that is worth caring about. But, it is not a problem that is uniquely caused by sportswashing, nor is it the most serious moral concern raised by the presence of Gulf money, so I’ll leave this aside for the rest of this post.

Equally, there are a whole set of worries about whether state ownership of clubs is something that takes them away from the fans: over time are we likely to come to view Newcastle United as simply a soft-power extension of the Saudi state, rather than a proud expression of the identity of a particular place and its people? Again, while a very real concern, I think this fits into a broader set of arguments about club ownership and whether it is right that football clubs are freely traded as commodities or brands, so is not just a concern that relates to sportswashing.

What is most distinctively problematic about sportswashing can be seen if we think about what the aims of the exercise are: as Wojtowicz, Fruh and Archer note, sportswashing is reputational in character, “an attempt to distract from, minimize, or normalize wrongdoing through engagement in sport” (if you’re the kind to want to read academic papers, their fuller discussion of the topic is available to read here). But any reputational gains are secured on the back of the players whose wages are funded or the fans cheering those players from the stand or watching at home: football and its participants become complicit in efforts to gloss over serious wrongs.

So how much of a moral problem is complicity within the project of establishing a positive reputation for the Saudi regime? Is it something that football players or football fans should be trying to avoid? And if we do want to avoid becoming complicit, what actions should we take?

Why care about Saudi money?

One response that is sometimes given by those who might want to play down the seriousness of sportswashing is to point towards the money that has already circulated within top level football clubs. Do we have any grounds for saying that Saudi money is worse than Roman Abramovich’s money, or even Mike Ashley’s money? There is a real point here: few of the people who possess the money to own a football club will have acquired it without some reliance upon exploitation, asset-stripping, tax avoidance or other forms of ethically dubious sharp practice. Whoever we support, it is likely that some form of dirty money lies behind them somewhere.

However, there is a difference between acknowledging that the ethical issues in discussion of football money are not blacks and whites, but rather endless shades of grey, and supporting a claim that all money is equally dubious so that no distinguishing lines might be drawn. There are undoubtedly, criticisms that might be made of money that has been made through operating a gambling firm, or a retail operation with poor labour practices towards its staff, but would anyone be willing to argue that there was absolutely no difference at all between money acquired in that manner and, say, an investment right now that came directly from Vladimir Putin? We don’t need to be able to hold up other owners as morally pure to commit to the idea that a line exists somewhere, beyond which funds are sufficiently tainted that we do not want them within the sport as this would create complicity with things we most certainly do not want to be associated with.

The question, then, in trying to assess how we should think about Saudi investment is to ask whether there are any associations of such a high degree of severity to cross this threshold.

The first thing to say is that we are obviously into different territory when we start getting full-blown states (through their sovereign wealth funds) owning football clubs. The opportunity for wrongdoing is just on a different order of magnitude for a state compared to businesses or private individuals: businesses follow (or seek to evade) laws; states make them and enforce them. States have armies, police forces and powers of coercion. This is why, when we talk of human rights abuses, we are generally pointing at state failures, either in improper use of power or failure to use powers well in controlling abuse by others within their boundaries.

And it is typically neglect or abuse of human rights that form the basis for the need to sportswash. The records of Qatar, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are frequently highlighted by human rights organisations for infringements of, or failure to secure, workers’ rights, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, etc. If a state needs to spend billions on sport in an elaborate reputation management exercise, you can hardly be surprised that what they have to hide is going to be unpleasant.

Yet, even by this standard, there is much to be appalled by when it comes to the Saudi state. As an absolute monarchy, its power basically rests in the figure of the monarch (currently King Salman), with accession decided by court intrigue between different factions among the House of Saud’s princes, such as that which brought the current crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) to his present prime role in the lineage, at the expense of the prior holder, Muhammad bin Nayef. The government is appointed by the monarch (MBS currently sits as the country’s Prime Minister) and serves at the monarch’s discretion, unchecked by any form of institutional scrutiny or popular input.

This is one of the things that makes it easy to be disconcerted by Saudi investment in football. The PIF sovereign wealth fund is basically controlled by the King (despite the Premier League claiming to have “legally binding assurances” to the contrary when authorising the Newcastle takeover), creating a direct link between human rights abuses carried out by the Saudi state and the money being pumped into the game. There is, therefore, a direct connection between the spending by Saudi Pro League clubs and the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, in every grisly detail we have subsequently found out about it, or in the 148 people who were put to death by the Saudi state last year, with public beheading still a common method of execution. We can also draw direct links between the denial of any legal right for LGBTQ+ people to express their sexuality and the desaturation of Jordan Henderson’s (more on him in the next post) rainbow armband in the video welcoming him to Al-Ettifaq. There is no easy separation between the money, the Saudi state and it’s actions.

But let’s delve a little deeper and tell another grim story (unfortunately, there are many to choose from) to help inform our evaluation of where we stand in assessing Saudi influence, with particular attention to its treatment of women and some of the much-trumpeted social reforms that have been enacted in recent years.

In 2017, a short video clip went viral on Twitter, filmed on a smartphone held at torso level, showing the shoulder and arm of a woman’s jacket. A woman’s voice is heard: “My name is Dina Ali, I’m a Saudi woman who fled Saudi Arabia to Australia to seek asylum. I stopped in the Philippines for transit. They took my passport and lock me for 13 hours just because I am a Saudi woman, with the collaboration of Saudi embassy. If my family come, they will kill me, if I go back to Saudi Arabia, I will be dead.”

Despite the efforts of many Twitter users to draw attention to her predicament or get official assistance, Dina Ali Lasloom was held at Manila airport until several members of her family arrived there. Witnesses later reported seeing her, visibly distressed, being pulled out of a room with her arms and legs bound with duct tape, her mouth taped shut and her body wrapped in a sheet as she was then carried onto a Saudi Arabian Airlines flight to Riyadh. The Saudi embassy in the Philippines sought to respond to the circulating social media information, describing it as incorrect, but confirmed that there was a “family matter” that led to a Saudi citizen returning to the Kingdom with her family.

Upon return, Dina was reportedly placed into a Dar al-Re‘aya — a ‘house of care’ tasked with imparting discipline and strengthening religious affiliation. Effectively, these are prisons for disobedient women, many of which operate in a highly abusive way.

Dina’s ultimate whereabouts and fate remain unknown.

The way Dina’s situation was handled is made possible by the guardianship system that operates in the country, which effectively consigns women to control by a male relative (father, husband, uncle, brother, even son), whose permission had to be obtained for many basic acts. So Dina’s choice to travel abroad was deemed improper, as she was doing so without the consent of her guardian.

In the period since 2017, there have been a raft of changes to the formal status of women in Saudi Arabia. Women have been granted access to services such as healthcare and education without the need for a guardian’s permission. Likewise, they may now obtain a passport or make travel plans without prior approval. Strict gender segregation of public spaces has been relaxed in a way that allowed more women access to employment or enabled them to attend sporting events. And, famously, since 2017 Saudi women have been permitted to drive.

This latter restriction had, in many senses, come to be symbolic of Saudi restriction upon women’s lives. Inspired by the Arab Spring, a homegrown movement of women — figures like Manal al-Sharif, Wajeha al-Huwaider, Loujain Al-Hathloul and Aziza al-Yousef — had begun to campaign for the right to drive, bringing the prohibition to wider prominence across the world. The provocative singer MIA chose to incorporate a reference to this, with the video for her 2012 single ‘Bad Girls’ aping the common drifting subculture of fast desert driving, but with women instead of men behind the wheel.

Within the context of the Saudis’ Vision 2030 strategy to move the economy of the kingdom away from a reliance upon oil, it is obvious why wider attention upon restrictions could be seen as an embarrassment. MBS has seen how areas within the Gulf, such as Dubai, have managed to open up to global tourism and financial investment in a way that created a viable economic future beyond oil, and is keen to follow a similar path. But, it is harder to project yourself as a destination or a suitable partner for business collaboration if your society is perceived as one of gender apartheid, with hard-line, or even backward, religious controls over its population. The fact that the apparent loosening of the guardianship system and repeal of the driving ban gained widespread approval from outside has helped to somewhat soften international perceptions, opening up possibilities, such as attracting some of football’s biggest names, that would have previously seemed impossible.

But, scratch the surface a little more and the liberalising narrative starts to look very shaky. Firstly, while there have been genuine changes to the way women are treated, with a loosening some of the guardianship restrictions in a way that promises additional freedoms to women, these are still effectively undercut by the fact that it remains a crime for a woman to disobey her guardian. What this means is that a woman is only able to take advantage of the new freedoms at her guardian’s discretion — if he wants her to remain in the home or to prevent her from travelling, she is still bound by these limits. As characterised by Megan Stack in The New York Times, what this amounts to is that Saudi “government will no longer legally force men to keep the women of their household under heightened control — but it won’t force men to emancipate women, either.” Cases like that of Dina Ali Lasloom, where a woman is going against the will of her family, would not be eased by any of the relaxations.

Beyond the question of whether changes have made a real difference, we should also look at the way that those who have advocated for change have been treated. While women were given the right to drive in 2017, many of those involved in the previous campaign for this entitlement subsequently found themselves subject to a harsh crackdown, with multiple arrests across 2018. In indeterminate periods of incarceration, activists report being subjected to torture in the form of solitary confinement, beatings, electric shocks, threats to life, waterboarding and sexual harassment.

This is part of a pattern in which the Saudi state has increasingly clamped down on any signs of citizen dissent. There is evidence of widespread use of arbitrary arrest, enforced disappearance and extended detention in poor or degrading conditions as punishment for even minor displays of criticism of the ruling regime. Salma al-Shehab, a Saudi PhD student at the University of Leeds who had returned home on holiday, was last summer sentenced to 34 years in prison simply for having a Twitter profile that followed the accounts of other activists and dissidents, and for occasionally retweeting some of their tweets.

We see, then, a double-edged nature to the way the Saudi state currently operates: to the outside world, there is an effort to present a face of being a forward-looking, exciting place that is opening up both to its own citizens and to the rest of the world; at the same time, anyone within the state who questions its rulers or calls for greater reform is ruthlessly brought into line. It leaves the impression that MBS wants it to be clear that the visions for the new Saudi are all bestowed purely as a result of his own magnificence and benevolence, that he is never acting in response to pressure from his subjects, or from outsiders looking in.

Here is where we can bring things back to football. In joining Saudi clubs, footballers are making themselves complicit in this process, essentially allowing themselves to be used as a propaganda tool for a state that still engages in torture, whose legal and judicial processes are opaque and arbitrary in their operation, who have contributed to one of the worst current humanitarian crises in the world due to involvement in conflict in Yemen, whose treatment of migrant workers is just as bad as the more publicised cases of Qatar and the UAE, whose treatment of women, LGBTQ+ people, and religious minorities remains discriminatory and dehumanising.

Drawing a line

I made the case above that it is implausible to claim we should never raise ethical concerns about the source of money within football, but rather it is always more about making a judgement as to when a line had been crossed into impropriety. Now, I am personally of the opinion that much of the existing money already within the game raises uncomfortable moral questions, so perhaps we should have been talking about these concerns for a lot longer than we have. Equally, it is important for us to be even-handed in our assessments and criticisms so as to prevent them from lapsing into simple xenophobia — for instance, we should be prepared to be critical of the fact that the UK has consistently been one of the biggest arms suppliers to the Saudi state, assisting in building its strength and power. But even taking these points into consideration, it seems clear to me that, from a football perspective, our worries should be increased when we are talking about money from state sovereign wealth funds, and that Saudi investment is the most discomfiting of any source of funds entering the sport so far.

Everyone in football, therefore, has reasons to be concerned about Saudi money, not just for its scale and the potential to distort the finances of the game, but also because of its inseparable associations with such a harshly autocratic regime.

The organisation ALQST provides detailed monitoring of human rights issues within Saudi Arabia. Further information and detailed reports about many of the issues discussed in this post can be accessed via their site.